My Little Communist Manifesto

Thank you so much, oh god what did I write, ok I'm pressing send—

Thank you, so, so much, for helping me achieve my single material goal for 2023—to hit 1,000 HR subscribers. My face literally looks like this right now C: Building this newsletter from scratch through its different iterations over the past three years has been an enormous catalyst in my life—it’s changed my conception of my politics, my desires, myself.

Please, excuse me, if you just followed me and this is the first post you’re getting blasted into your inbox, because today’s writing is something I’ve never done before on HR: a stream-of-consciousness that winds around communism, ambition, my career, and a favorite movie that ties it all together (ish), resulting in a TL;DR thesis of: Life is Hard, Green Day is Good, Politicians Are Lobotomized, Let’s All Love Each Other.

Luckily, the HR back catalog is jam-packed with light, shoppable, photo-heavy posts for your perusal, (here is a grab bag of random favorites) and if you need more, you can access bonus posts by supporting the blob for $2 (or less!) a month here OR sharing your favorite HR IG post on your story and tagging me—I’ll comp you a month of access to the entire archive of bonus posts. There will always be two per month, and always at LEAST two totally free posts per month, at least until I sell out to Crunchyroll or Western Union, my two most coveted sponsors (call me, Mr. Crunchy!).

Thank you for being here, for letting me indulge in this introspective (unedited, haha, totally an artistic choice and not an I-need-to-release-this-before-I-think-too-hard compulsion! It might get a little freaky down there) rant, and for helping me realize my long-suppressed ambition: to be the most conflicted communist of a fashion dweeb on this side of Substack. Half kidding. We’ll be back to our regular programming next post.

In any case:

Years ago, in college, I did someone else’s school assignment (long story, pleading the fifth, tragically one of, if not the, best assignment I’d completed in years), and for it, was required to watch Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, a 1927 silent film in the tradition of German Expressionism. I will disclose with no shame that I watched it on 1.5 speed (I had an essay to write!), but I was shocked at how moved I was by the opulent, dramatic representation of capitalist dystopia the film presented through its sets, practical effects, and performances, sans all but the most bare-bones, written interpolations of dialogue.

Ok, here’s a fashion sidebar: maybe one of the reasons I’m so drawn to opulence and drama in fashion, e.g. Lumps and Bumps and Enchanted Metonyms, is because it’s the most personally accessible way I can think of to cope with our own, current capitalist dystopia through aesthetic modulation—and see, I told you this would be a rough ride, because I realized while writing this paragraph I’m essentially saying I’m “Looking camp right in the eye.”

I knew at the time that the film was communist propaganda, without words or almost any knowledge of its actual historical context (hey, I didn’t take the class!), simply from the alignment of my own communist sensibilities with the heavy-handed allegories and visual metaphors used by Lang to make sure no one accidentally came away from the film thinking industrial capitalism rocks (e.g. after an accident kills several workers, the film’s protagonist hallucinates the offending machine as a monstrous, sacrificial temple to which the workers are fed by indifferent supervisors).

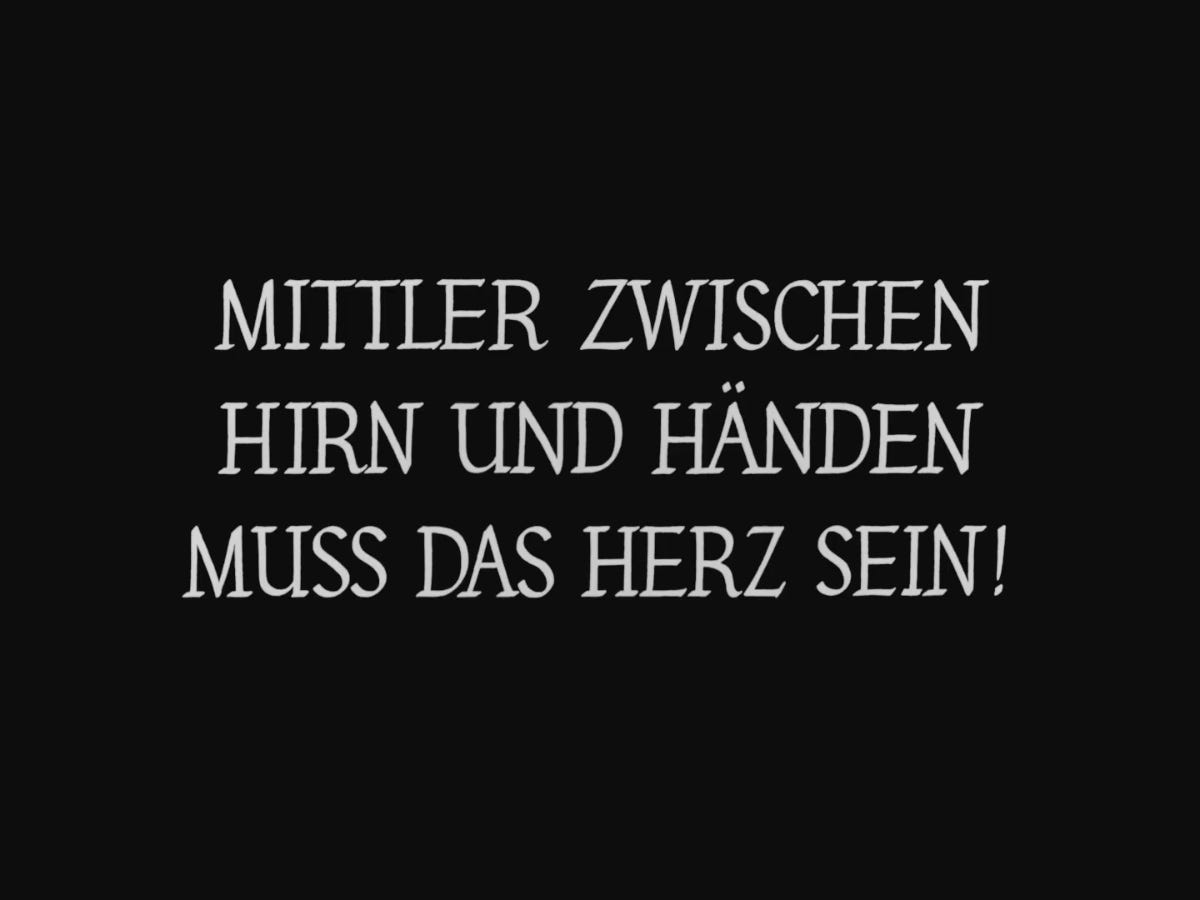

However, the moment in the film that went on to a) become my Twitter banner photo for going on five years and b) subconsciously influence the past five years of my emotional and aesthetic relationships with the communism I’d adapted five years before that comes in the very last moment of the film, and is simultaneously more blunt and more oblique than any of the other moments of class-conscious pageantry Metropolis is comprised of. It’s a single title card, flashing onscreen after the protagonist convinces the man who represents Mr. Monopoly-level capitalism and his foil, the consummate beleaguered working man, to shake hands:

“THE MEDIATOR BETWEEN

HEAD AND HANDS

MUST BE THE HEART!”

On a surface level, this quote is super pop-punk in a way that appealed to me as a noted Green Day fan and Pisces. It’s an imperative, but an emotional one—it doesn’t require orthodox praxis or too much critical thinking at first brush, just a big, tender ‘ol thing in one’s sternum, which we all have pre-loaded into our chest cavities at birth. Political-feeling statements that don’t ask much of you beyond your baseline existence are so comforting. This is why people who are genuinely engaged in social (not necessarily governmental/formal) politics are almost always depressed and people with political optimism can refer you to a great lobotomist (This is, incidentally, why it almost never seems like “politicians” are doing the kind of “politics” that we plebs consider most dire—they’ve had to sever their proverbial frontal lobes so as not to completely disintegrate into acrid despair).

To be required to make existential and ontological decisions with no objectively “right” answer, to have to make material or emotional sacrifices to oppressive, bad faith systems and persons in order to stumble through life without being physically or spiritually executed by these entities on the basis of your marginalized or capitalism-resistant traits, to do all this flawlessly and still come face to face with the twin traits of suffering: inescapable agony and an ultimate, almost-more-brutal vacancy—these are the constant, autopilot tasks that become habitual, if not compulsive, in a brain that commits itself to what “politics” can actually mean in our lives, which always comes down to the difference between life and death (or a life worse than death) at the end of the day.

Today, I realized that for five years, I’d gotten the gist of that exclamation, “THE MEDIATOR BETWEEN HEAD AND HANDS MUST BE THE HEART,” totally wrong.

I used to think that having absolutely no ambition was one of my personality traits. I would always shudder when I’d see advice column questions or reality TV personalities grappling with such issues as whether or not to give up their dream jobs for the alleged love of their lives, or vice versa. I could not comprehend an existence in which I felt a fraction as passionate about work I’d done as I did about the people I loved, and the idea that anyone could even place the two within a ballpark’s distance of each other was, to me, simply a symptom of capitalist brain rot: the fact that clocking in every day could be considered in the same universe as kissing a loved one was truly unthinkable.

I dated many people who did, in fact, see these two facets of their lives as existing on the same plane, and when I was much younger it disturbed me: I could not have cared less about my career, my only identifiable aspirations in life were to help and brighten the days of as many people as I could reach, find some sense of peace despite my struggles with mental and physical health, and die leaving behind people who would genuinely miss me. Meanwhile, I felt like I was on tenterhooks, aware that most other 20-somethings were hand-wringing over whether or not to ditch their partners of half a decade to pursue…law????? Coding????? Or, god forbid, economics??????? To cope with this feeling of relative social vulnerability in the company of my peers, I decided to forcibly make peace with my lack of ambition, sublimating it into my politics and personality. I saw all ambition as inherently tied to a hegemonic construction of notoriety and wealth, and therefore, its lack as the only way to genuinely live in my desired truth of a non-hegemonic happiness.

I would still experience mysterious pangs when a partner or a friend would announce they were going to apply for a Master’s (ok, this one isn’t entirely my self-delusions, I did get saddled with an insane amount of debt at age 17), or on the once-yearly occasion of my logging in to LinkedIn, or upon listening to an interview with an artist I loved in which they espoused the value of their unwavering ambition. I tried to ignore them.

I only realized last year, after two years of writing Human Repeller in some kind of pandemic-induced fugue state, with no clear goals or aspirations for this project, that I wanted to be a writer and editor in and around the fashion world. I’d loved, and showed talent in, both fashion and writing from a young age, but (I can hear my mom smirk from across two hemispheres right now) I shied away from ever investing my time and energy into something I might actually be good at. I didn’t want to be good at work. If I had to do it (and by god, I did), I wanted work to be simply a pill I had to swallow every day, a rote chore, nothing that poked at the mysterious, panging bear I knew was hibernating in my sternum. I did (and really enjoyed) service work through college. I invested years and tears and more money and brain cells than I care to recall into trying to get a job coding. I ended up with literally nothing except a Goliath debt, a BFA, and a resume of barista gigs to show for over two decades of trying to fit the square peg of my brain into the round hole of my way of thinking. Oh, and this stupid, pointless blog, then on Wordpress, which at the time no one except my mom and grandma read (thanks, Mom and Grandma, I love you both so much!).

One day last year, I realized what the pang was: abject terror of being truly vulnerable in situations where I felt I was being genuinely judged based on my abilities, instead of on some vague gestalt of “self” I could easily dress up with a survival mechanism-generated charisma. I’d never been afforded the chance to be in one before I got my job at Magasin based solely off the merit of my work—I had nothing on my CV to back up my writing or editorial abilities, no social media following as corroboration, not even a corresponding degree. At previous jobs, I’d get the odd positive feedback, but it was all about how I was vaguely “smart” or had “potential,” which are obviously nice sentiments, but it was never like I had something that I was actually, uniquely, irreplaceably bringing to the table. I felt like the factory worker I’d wanted to be, like the disembodied “hands” in the title card, and I fucking hated it, in spite of myself.

I am so thankful to Mag’s creator, the brilliant Laura (and have probably told her this too many times) for allowing me the chance, with no track record, to start building my resume, portfolio, and skill set for this career path I’ve shakily set off down. Working that job, now as News Editor for Mag, and in my new role as Managing Editor for passerby, does have a huge catch, however: the catch I was afraid of snagging myself on the whole time I resisted my ambitions towards writing and style.

It’s kind of nice to be able to divorce yourself from your labor like I could in service and coding, because then, the realities of alienated labor as per Marxy Marx don’t feel so personal or high-stakes, they don’t feel like such a giving-away of the self, so mortifying. But now I realize that unless you find a way to genuinely innovate or to be creative or constructive in your more rote, detached job (thus giving up the advantages of its rote detachment), working without a certain level of passionate vulnerability precludes an ambition separate from sheer financial aspirations, which is in fact possible—the two intertwine inseparably, of course, but they are distinct.

Under capitalism, as we are now, you (unless you have a trust fund, in which case, consider signing up for a $2 paid sub to HR ;)) must either sell your hands (becoming a proxy body of a boss, a factory worker, an automaton) to save your head, or sell your head (allowing your passions, beliefs, and other vulnerable aspects of your self to be valued based on the whims of the market) to avoid being reduced to a pair of hands. Under all systems, we eventually have to do work we don’t want to do, which isn’t an indictment of anything, but “doing chores” is not the same thing as “feeling constantly emotionally, temporally, and spiritually robbed by indifferent systems.” This can also happen in a planned economy, as history has shown us, but my belief is that the ethos and ideals of communism don’t preclude the union of head and hands, while capitalism, by necessity, does.

This is one of those choices that has no correct, not even a “good,” answer. I found being a barista extremely fulfilling, if harrowing and humbling in the way all service work in NYC is, until I fucked up my body too badly to continue. However, I always felt that pang of an ambition I was too scared to acknowledge, the thought that I didn’t really want to commit to automaton-hood in exchange for being protected from the mortification of commodifying my own brain and thoughts. And god, is it mortifying—even just writing this blog, which I make almost no money from and hardly ever even spellcheck, is humbling. Making my little collages to post on Instagram for 30 people to see is humbling. Working two jobs, plus freelancing, for less than half of what I made in a year as a non-profit admin (one of the reasons I live in Argentina)? Extremely humbling.

Because I truly feel like this is the most valuable thing I can offer the world. I can be around in emergencies, I try to be a good friend, partner, child, sibling, etc., and I hope against hope that someday I’ll have paid off my debts and have a career that allows me to proliferate money to those who need it—but at the end of the day, the only thing I have within me that only I can give you is the way my brain dresses up and puzzles together words, and to an extent, clothing. To see all I have to offer splayed out where even people who don’t like or support me can peruse it at their leisure in exchange for the beginnings of a career that can’t functionally support me yet? Say it with me, now: H u m b l i n g !

And to have to reconcile with all this while your chosen path and the passion foisted upon you by forces beyond your control (for a lot of us, probably Tavi Gevinson, let’s be honest) is explicitly considered a frivolous waste of time by the Very Guys who formulated the seeds of your worldview, and almost always necessitates conspicuous materialism? Well, when you look at it sideways, it’s pretty funny, actually.

I guess this has turned into My Little Communist Manifesto, haha, and I haven’t said anything really novel or insightful, but I really enjoyed taking this reflective moment to share a little glimpse of the head and hands (and…heart?) behind this blob with you. At the end of the day, the ideals and possibilities espoused by communism are rooted in the heart, in the desire for exploitation to end and love to proliferate, which is the NECESSARY TOOL to facilitate the coexistence we should all be afforded by society: the ability to dignify and revel in both our hands and our heads as much as possible, without feeling the need to sever our own frontal lobes to ignore the dichotomy capitalism forces upon us. Per the actual Communist Manifesto: “In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.” That’s some punk-poptimism if I’ve ever heard any.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on any of this, if you make it this far. The comments below are a great place to chat, but I can always be found here, too.

Thank you, again, so much, for everything. For being here, most of all.

<3 HR

Thank you so much for writing this. I’ve been having this crisis for the past year... bogged down by the existential question of what I want work to mean to me and what it means in our capitalist system. I was on the road to just wanting to disconnect- thank you for reminding me why I’m pursuing the work my heart desires. You’re right, it is humbling. But you’ve reminded me that it’s worth it. Thank you.

God em this was SO good!!!!