The Transcendent Glory of Impotent Masculinity

Thoughts on a new masc aesthetic that pulls ALL its punches and looks great doing so.

Hi. Today is….a little shark-jumpy, so I made it free. Hope you enjoy, or at least abhor. No apathy allowed.

If you like these posts, please let me know by liking and commenting here or on HR’s Instagram, subbing to the HR Substack (this) for free, getting bonus posts for seven bucks a month, or for ZERO DOLLARS, share (tag me if on IG so I can see and thank you)!

If you cannot afford the $7/month, which I totally understand, respond to any of my email sends and I will get you a $2 subscription or comp you, whatever you need. HR is for everyone!

Thank you SO MUCH for your support, whatever you are able and willing to do to help is extremely valuable to me and I’m honored to be a small part of your life on the web.

Clarifying note: “Masculinity” and “femininity” in this essay refer to the abstract, amorphous societal conceptions of them including forms, semiotics, conventions, mythologies, phenomenologies, not to experiences had by men or by women. Anyone of any gender interacts with both masculinity and femininity on a daily basis, whether or not they choose to identify themselves anywhere within the binary gender system.

Another clarifying note: This is an unedited, unhinged, probably unwarranted ramble that I didn’t want to try to mold into something more coherent or cutting-edge for an official publication, so if it makes no sense, hey, this post is free! And if you’re only interested in how this relates to fashion, check the last two paragraphs. We’ll be back to scheduled programming with a paid post very soon.

Masculinity, as conceived of writ large, is dominant, aggressive, violent and virile, individualistic, cold, and simple. Most art that explores the psychology of masculinity focuses on deviations from this form or how, when strictly adhered to, this masculinity inevitably self-destructs, and fashion up until the past ten years has relegated masc-ness to a uniform fitted to accommodate these qualities. Happily, a masculinity defined by patriarchal, capitalist demands seems to be loosening its grip on the worlds of art and style, leading to everything from detaching the conception of impotence from inherent shame to TikTok’s babygirlification of everyone from fake vampire Astarion to real human Keanu Reeves. It’s a whole new world out there for the masc facets in us all, but in a neck-breaking U-turn, let’s go back to 1949:

Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman exemplifies the aforementioned inevitability coded into masculinity. As per Sparknotes, “Willy’s failure to recognize the anguished love offered to him by his family is crucial to the climax of his torturous day, and the play presents this incapacity as the real tragedy.” Millions of high school freshman will read this plot summary before a quiz on this play they’ll never read, but they will learn that the “real tragedy” of Salesman isn’t Willy’s suicide, or the hurt he inflicts on his family with his infidelities, or any other action Willy takes over the course of the play. The tragedy lies in his incapacity for receiving, internalizing, and prioritizing the love he is offered, a trait that is inextricable from the two things he does prioritize: his masculinity and his standing in the schema of capitalism.

Looking more closely at what is commonly accepted as the essence of masculinity, one might realize that every trait listed above (dominance, aggression, individualism…) is more intrinsically capitalist than masculine. Masculinity did not evolve by necessity into the incapacity to receive love; or preemptive, performative aggression; or an obsession with rationality at the expense of acknowledging emotional realities. These are all traits that, as modeled by Willy, aren’t conducive to survival. The unquestioning conflation of transcendent masculinity with its capitalist manifestations gives it the air of inevitability that makes Death of a Salesman so tragic.

Since masculinity in this patriarchy is not a typically victimized way of being, it is harder to make art about it. Art is more likely to use “masculinity” as an assumed backdrop to perpetuate or take down than to interrogate what a masculinity independent of hegemony would look like. Art specifically about masculinity is usually a “queering”/challenging of its norms (or it’s actually about femininity/lack of masculinity as it manifests more or less queerly in male-identified people). Art not specifically about capitalist masculinity, but by someone who adheres to its aesthetic straightforwardly (i.e. Bukowski), doesn’t usually attempt to access a masculinity beyond itself.

However, there are certain artists, and more recently, fashion designers, who have succeeded in evoking a transcendent masculinity. It’s not completely fleshed out, nor is it a fraction as Herculean as its societal ideal, but the masculinity envisioned in these works, though it certainly is never free of the capitalist masculinity and its conditions, seems to suggest a more compelling, more glorious even, way of understanding masculinity could exist outside of what modern, Westernized society has known it to be.

John Berryman’s poetry tears at the seams of material/profane masculinity. His life was largely defined by many of its facets: violence (his father shot himself to death outside Berryman’s window when he was 11 years old), virility (he is known for his serial infidelity), a profound sense of individualism evident in the alienation he describes in his autobiographical writings. However, in his poems Berryman creates characters such as Henry who are decidedly masculine presences yet less blinded by self-aggrandizing adherence to capitalist ideals. His men are kind of useless. In the first poem of his seminal collection The Dream Songs, “Huffy Henry” hides, sulks, is “pried open for all to see.” The image of a man rent open, flayed and spread out on the wall like a poached beast, is a repeated motif in the rest of the Songs and his other works, as are other descriptions of the casual but brutal defilement of men who may or may not be Henry. In Dream Song 8, an unnamed “they” “took away his teeth,” “...lifted off his covers till he showed, and cringed & pled/to see himself less,” and finally, “They took away his crotch.” The men Berryman writes are typically impotent in some way. Henry is described as “unkissed” (DS3), he lusts over a woman in a restaurant and, while ogling the “slob” she’s sitting with he contemplates his own failure with women “Where did it all go wrong? There ought to be a law against Henry.”

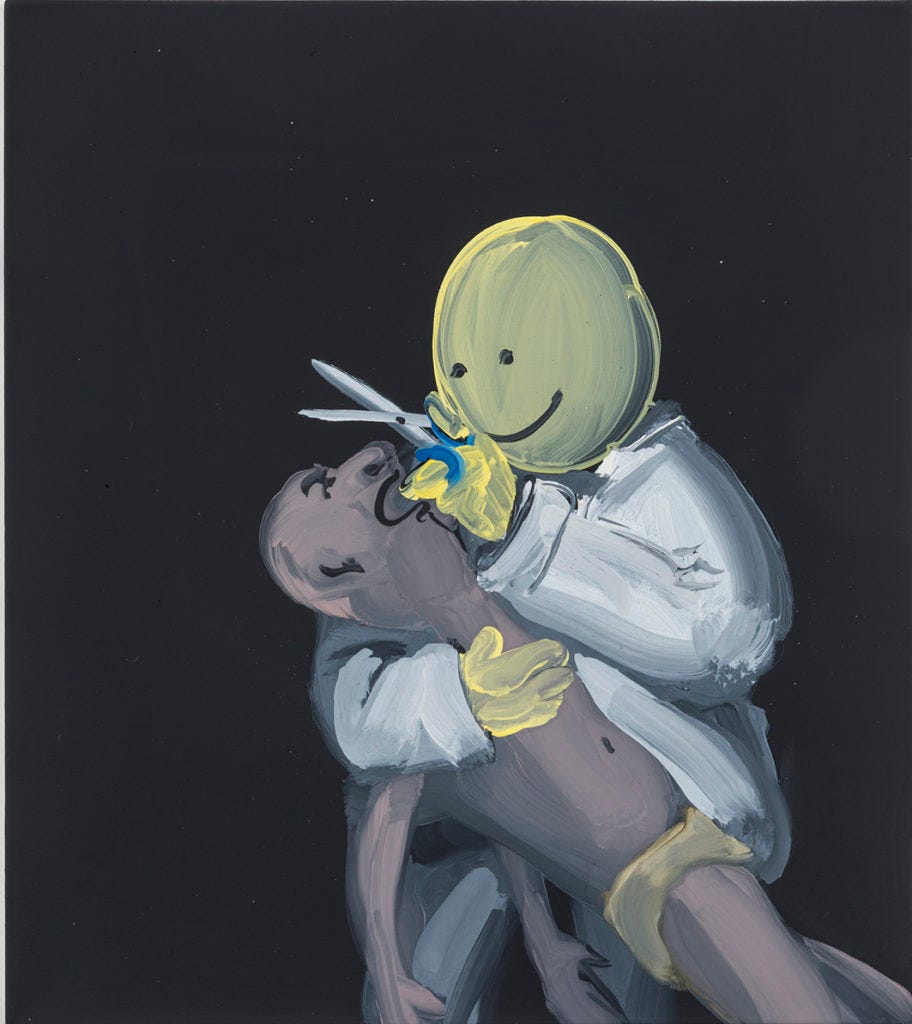

Berryman’s poetry reverberates through the mind’s eye as if illustrated by Tala Madani. Madani was born in 1981 and is an Iranian woman—her art isn’t preempted by an understanding of the world defined by an identity considered “default” as Berryman’s is. This allows her to make Man Art without as many disclaimers—it’s virtually impossible for the subject she fixates on in her work, masculinity, to be accepted at face value when her identity is taken into consideration. Her art certainly doesn’t perpetuate an unquestioning validation of capitalist masculinity but it isn’t a straightforward rejection of that masculinity as oppositional to Madani’s identity. The men Madani creates in her paintings and animations aren’t mere reactions to femininity—she hardly ever includes figures or symbols that evoke femininity at all in her work. Her men are vulnerable: doughy, translucent, often naked. She paints them fraying at the edges, dripping down the canvas, illuminated from within by a flashlight stuck in an orifice. Even the sexed images of genitals, body hair, and gestures that would typically read as homoerotic are neutered in Madani’s vision.

A guiding force behind this neutering is Madani’s view of the relationship between adults and babies—she is interested in “the potential of what kids are capable of and what adults are capable of.” She cites how stories about kids replacing/overthrowing adults such as Oedipus Rex are fundamental to Western culture but many stories in Iran are centered around adults killing children, sometimes accidentally. The men she paints are often interchangeable with the babies she paints, save for the possibility of some paltry or cartoonish facial hair that serves to further amplify their bald, bulging infantilism.

If Madani’s intention were to denigrate or mock these pathetic figures, she could, easily and unequivocally. Adding a single fully clothed, composed, authoritative figure to one of these paintings would make them about shame, emasculation, masochism, but because every single character, from the figures enacting to those receiving the actions (i.e. men painting, peeing on, preparing with a fork and knife to eat one another), is shrouded in her specific aesthetic of impotence.

In one painting, “Fork in Tattoo” (2006), a central male figure has his back exposed to the viewer, looking over one shoulder in a glance that suggests self-protection, while another man reaches around in a half-embrace, seeming to draw blood with a fork dug into the outline of a cake tattooed on the first man’s back. The man with the fork hides half of his face behind the tattooed man’s shoulder. Saatchi gallery’s commentary on this painting is that “their fetishised violence [is] rendered tragic and flaccid, contriving the phenomenon of male bonding an embarrassing and lovable spectacle.” “not knowing who the aggressor is, or if they’re liking being victimized, being pulled at…”

This conception of the impotence of masculinity, because it is not the impotence of men, rather, masculinity as characteristic of a paradigm that people of all genders operate within, differs from but still relates to Jack Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure. The book explores the concept of failure as a valuable and liberating experience within the context of queer culture and theory. Halberstam argues that embracing failure, in all its pathetic impotence, can challenge societal norms and expectations, especially those related to success, heteronormativity, and traditional gender roles. The book encourages readers to reconsider the value of success and to explore alternative ways of understanding identity, community, and resistance, ultimately celebrating the idea that failure can lead to new possibilities and forms of living.

Several fashion designers have explored these possibilities by presenting a spin on the aesthetics of masculinity, refiguring them as vulnerable or impotent in commercial imagery or the clothes themselves. Bimba Y Lola and Palomo Spain recently released brass knuckles fashioned into budding roses; Foo and Foo’s now sold-out Boner jeans scrunch stiffly and awkwardly up and down the sides of the wearer’s legs, protruding like offhand erections; Ludovic de Saint Sernin’s see-through boxers introduce lingerie into a masculine visual vernacular; and schoolgirl-ish pleated skirts by Thom Browne invite the specific objectification that traditionally girly Catholic school uniforms hasn’t been able to escape from, among many other instances of definitively masculine clothing that definitely subverts the popular ideals of masculinity as laid out above.

Beyond “nonbinary dressing” (ayo, who wrote about that recently???), this retooling of the intrinsic aesthetic nature of masculinity as something defined, at least at times, by vulnerability and impotence, is a fascinating game art and fashion can play with gender expression, leading to, from the outside in, new forms of being in our own private masculinities. Of course, participating in the capitalistic endeavor of pumping money into the fashion industry isn’t revolutionary, but I’d never claim to be affecting material change within the confines of this blog, just positing different angles from which we can consider fashion.

Thanks for letting me think at you.

<3 HR