Treat Your Clothes Like Pets

Thoughts on how a closet can be conducive to materialist dialectics, feat. Varvara Stepanova and the Constructivist clothing fiends.

Hey! Nothing to say up front except that this week’s post is a little noodle on the merits of centering clothing in a dialectical materialist framework, focusing on Constructivist fashion designers of the 1920s, something that’s been on my mind all week. See you at the bottom of the screen!

If you like these posts, please let me know by liking and commenting here or on Esque’s Instagram, subbing to the Esque Substack (this) for free, getting bonus posts for five bucks a month, or for ZERO DOLLARS, share (tag me if on IG so I can see and thank you)!

If you cannot afford the $5/month, I totally understand—respond to any of my email sends and I will get you a $2 subscription or comp you, whatever you need. Esque is for everyone!

Thank you SO MUCH for your support, whatever you are able and willing to do to help is extremely valuable to me and I’m honored to be a small part of your life on the web.

As I’ve suggested in this newsletter before, a large aspect of my fixation on clothing is based upon the idea that it’s the third most intimate material we interact with on a daily basis, the second being the food and medications we must put inside ourselves in order to stay alive; the first, our human bodies themselves. I’ve written about artist Paul Thek’s formative experience with encountering human remains-as-material in Capuchin catacombs: “He picked up what he’d thought was a piece of paper — it was a human thigh. Thek said ‘We accept our thing-ness intellectually, but the emotional acceptance of it can be a joy,’” and I’ve tried my best to formulate thoughts on the poignant objecthood of garments that I see potential for in the finicky philosophical school of Object Oriented Ontology.

This might be as far as any attempt to cohere my identities can be taken—my Substack bio has, for years now, read: “communist, clothes lover, constantly reconciling.” In the back of my mind, something has continued to itch: materialism, the conviction that the relationships between physical entities is the underpinning of everyone’s lived experience, is such an integral factor in the trajectory of leftist thinking—it’s strange that clothing, a material I’d argue is more intrinsic to our experiences of the world than almost any other technology, is such a danger zone, devotion to exploring it seen as ideologically incompatible with most sects of leftism as such.

But isn’t this all the more reason to center fashion in our attempts to wade through the muck that our current world entails, in this moment where we all feel haplessly beholden to capitalist pageantry and abandoned by the inherently communist/socialist values of…well, community and sociality? Materialism was reformulated by Marx scholars into “dialectical materialism,” a way of thinking predicated upon the idea that ideology should spring from an understanding of the material realities of the world in all their contradictions and paradoxes (instead of a dialectics, or investigation of the truth, sequestered in the world of ideas with the thought that if everything can be ironed out on the drawing board, these “sorted” conceptions of life will trickle down and play out in material terms).

The fetishization of material objects isn’t the end point of dialectical materialism, a world that isn’t designed to murder 99.9% of its constituents is, but the tension between object fetishization and disgust with the means of production we’ve been sold as the only viable method to create these objects seems to me a real breeding ground for valuable ideas, both political and aesthetic. I think this is why there’s such an undeniable tie between leftism and nerdiness (to speak nothing of my old friend, straight-up autism): people who tend toward the belief that the complexities of our shared material reality are where there’s a chance of finding genuine connection, or at least momentary solace, in this harsh world, are more likely to hyperfixate on, say, trains, or acrylic nail sets, or postage stamps.

Object fetishization is a haven for people who feel ousted by the mawkish realities of our delusional political systems, but in its ties to marginalized identities and unabashed attachment to ornamentation, seen as an inherently bourgeois endeavor, fashion has been discounted as a respectable field of leftist experimentation.

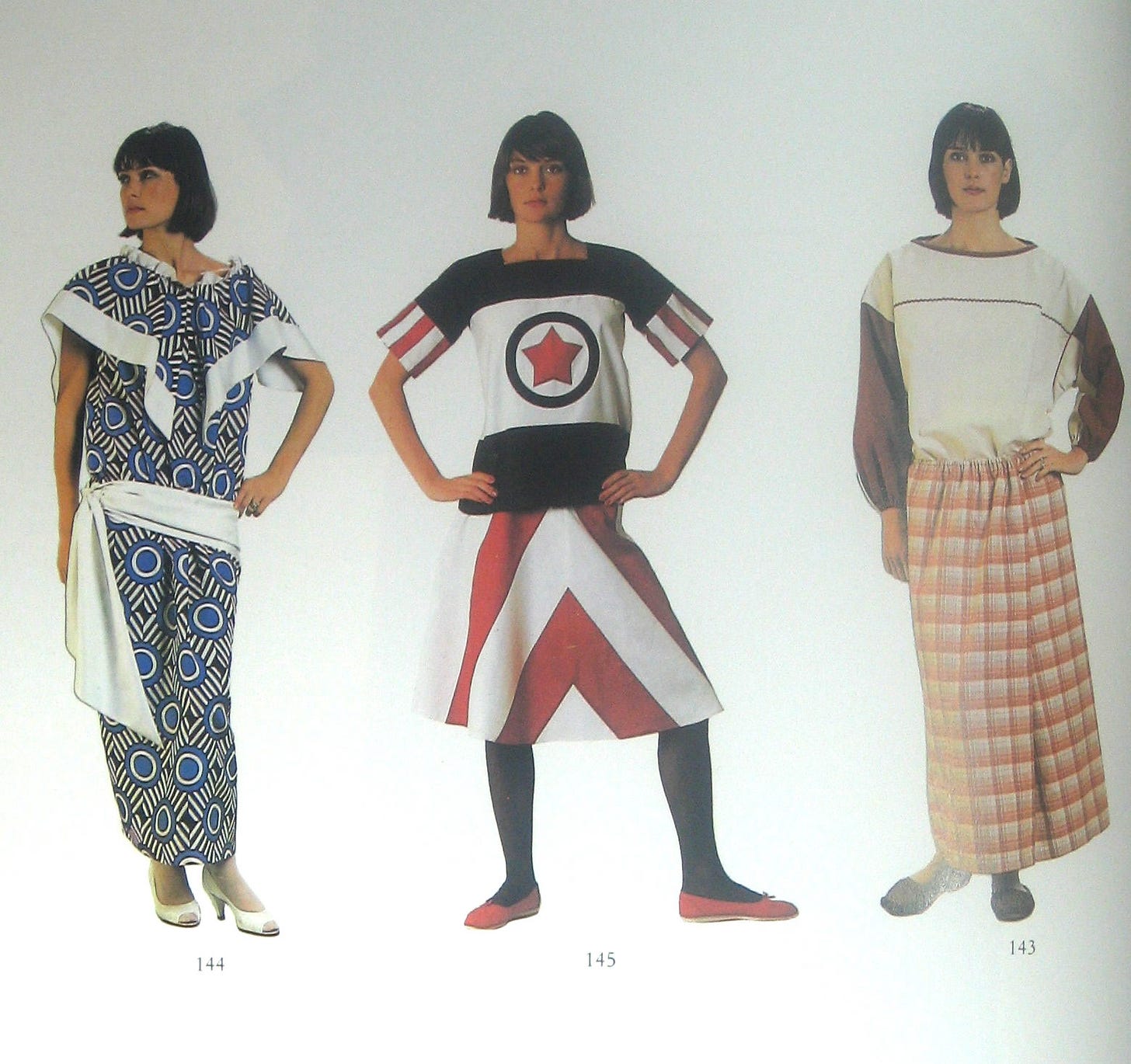

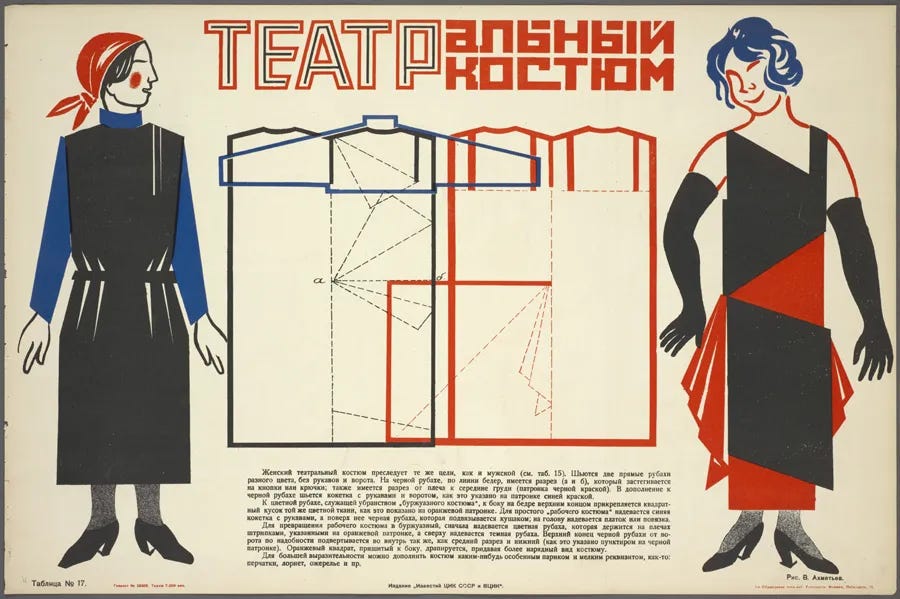

I caught up with my brilliant friend Ben this week (their chapter of BDS was recently largely responsible for a ground-shattering Intel divestment from Israel, incredible), and they reminded me of a missing link I’d been obsessed with for a few months back in 2021, then promptly forgot, as things go: the 1920s Constructivist Soviet fashion designers, most notably Varvara Stepanova [below], who sought, as Chris Randle writes, “to collectivize the economy of desire. The workers deserved both bread and satin.”

Not only did the fashion-oriented Constructivists (members of the early-20th-century art movement who didn’t necessarily share its predilections toward austerity) believe that clothing was a decent, understandable thing to value, they understood its physicality in a way similar to my own OOO-inflected thesis above: as “a total material environment in which the living human material was to act,” as per Stepanova. Designing garments that eschewed subtlety in favor of overt signification, with patterns and cuts that mimicked the gestures a wearer might make while in each piece, the Constructivists prioritized creating clothing that compounded upon lived experience, reinforcing the senses instead of dulling them.

This commitment to making clear what already exists, making even the smallest movement of a body clear as opposed to trying to smooth out every wrinkle that makes up a human being, reminds me of what Michaela Stark does with her art and now her RTW line, Panty, in opposition to, say, Skims—Stark’s fixation upon adding definition to the preexisting bulges, rolls, and folds that comprise bodies of all sizes feels aligned with Constructivist aesthetics against an industry that prioritizes shapewear, body-slimming gear, seamless construction.

The reason Stark’s work wouldn’t actually jibe with Stepanova’s is that an important tenet of the latter’s work was a neutralization, or neutering, of the human form, divesting it from sexuality, which was seen as an unnecessary, superfluous element of fashion. I disagree with this and think a lot of Soviet sexlessness was, essentially, reactionary cope funded by an understandable disgust with the fact that “sexy” at that time (and maybe still?) had become synonymous with “marketable,” obviously not what they were going for with their reimagination of the fashion industry. Maybe I’ll blather on about this particular point later, in a different post.

Something I found really interesting in the Randle piece was the revelation that “garment workers often represented ‘the radical core’ of leftist groups: apprenticeships made the city intimate to them, and when their masters sent them out with a delivery, they confronted the bourgeoisie inside its own houses.” Of course I knew that garment factories, especially in early-20th-century NYC, were sites of class fomentation and union organization (even passing knowledge of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and its reverberations makes that much clear), but in my recent work as a styling assistant here in the city, I had this exact train of thought. Traipsing around to lavishly decorated ateliers funded by who-knows-what-money, sweating onto the garment bags that’d leave red marks on my arms after three hours of lugging, to be greeted (sometimes! Sometimes the people who work at a design studio are really cool and much more put-upon than I) by a perfectly-coiffed PA who’d gingerly take the hangers from my hands, looking as if I’d handed them a dead cat, certainly made me feel like I was confronting *something* insidious, and certainly made me feel more-than-conscious of my lowly stature in the eyes of not just the industry but the city itself.

However, since I was lucky enough to work with artists who see styling, photography, hair, makeup, and set design for a fashion shoot as an opportunity to create spatial, active sculpture instead of a showcase of inertiatic commerce with no relation to the human body (apparently a rare luxury in the styling assistant world), in this work I was able to conceive of clothing as Stepanova idealized: “Today’s dress must be seen in action,” she wrote. “Beyond this there is no dress, just as the machine cannot be conceived outside the work it is supposed to be doing.”

Though action is required, in Stepanova’s eyes, to reify the existence of a garment, there’s also a contradictory impulse in Constructivist fashion that goes back to my OOO spiel—the impulse to view and treat clothing less like an object for consumption and more like a pet one has been charged with caring for and cohabitating with. This is a really cool lens through which to view efforts toward sustainability in fashion, if the whole “imminent world conflagration” thing isn’t enough of a selling point for you and you need something a bit more esoteric to convince you to hang on to your clothes, wearing them to pieces or mending them as needed.

Stepanova once wrote that “fashion accessibly offers a set of the predominant lines and forms of a given slice of time,” a phrase that to me suggests that collecting and curating a closet is as valuable a cultural endeavor as collecting paintings or rare books, if not more imminently zeitgeist-y, and with all their physical intimacy to our most literal selves, how clothes record our movements, injuries, attentions, and passages through time, I can’t think of a material more worthy of dialectics than a garment. If treated as a pet of sorts, a humanoid entity with a body that bears witness to and records into its weft our highest and lowest moments, a garment may well be one of the most truly valuable objects we interact with in our time on Earth.

Thanks so much for reading this—I’m quite obviously not a scholar and most of this is just regurgitating thoughts I’m sure two million other people have on a daily basis, but I still don’t think Stepanova and co. get enough air time, so hopefully this was a generative endeavor. Thank you so much for being here, always.

<3 ESK

great piece! this really helped me understand and contextualize my personal connection to clothes/fashion. "today's dress must be seen in action" really struck me: of course there's value in beautiful couture pieces that aren't meant to be worn over and over, but each person's clothes that they wear throughout their lives hold just as much history.